and dairy industry) on human health. It can be considered to be a companion piece to an earlier film by Andersen and Keegan Kuhn, Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret (2014), which focussed on the impact of the animal agriculture industry on the environment. Both films feature Kip Andersen as an investigative reporter talking to various spokespeople and lobbyists in the animal agriculture industry, as well as figures from environmental organizations (like Greenpeace and The Sierra Club, in the case of Cowspiracy) and from human health organizations (such as The American Diabetes Association, in the case of What the Health). Andersen also spoke onscreen with a number of doctors and investigative world experts, government officials, and others who are outside those specific organizations but who are impacted by the effects of meat and dairy industry food production. And both films come to similar conclusions – the meat and dairy industry is fundamentally harmful to human welfare.

and dairy industry) on human health. It can be considered to be a companion piece to an earlier film by Andersen and Keegan Kuhn, Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret (2014), which focussed on the impact of the animal agriculture industry on the environment. Both films feature Kip Andersen as an investigative reporter talking to various spokespeople and lobbyists in the animal agriculture industry, as well as figures from environmental organizations (like Greenpeace and The Sierra Club, in the case of Cowspiracy) and from human health organizations (such as The American Diabetes Association, in the case of What the Health). Andersen also spoke onscreen with a number of doctors and investigative world experts, government officials, and others who are outside those specific organizations but who are impacted by the effects of meat and dairy industry food production. And both films come to similar conclusions – the meat and dairy industry is fundamentally harmful to human welfare.What the Health begins with Kip Andersen introducing himself and confessing that he is a recovering hypochondriac. He used to compulsively follow public prescriptions from the meat and dairy industry, such as faithfully consuming three full glasses of cow’s milk every day (I used to do that, too). Later in the film we are shown, in fact, that cow’s milk is nutritionally very different from human milk and is not really suited for human consumption. This is an example lesson that almost everyone can relate to.

further disturbed to see that they not only ignore WHO’s announcement but that the American Cancer Society seems to explicitly endorse the eating of processed meat. When he tries to contact the American Cancer Society about their policies on this issue, they brush him off and refuse his requests for an interview.

further disturbed to see that they not only ignore WHO’s announcement but that the American Cancer Society seems to explicitly endorse the eating of processed meat. When he tries to contact the American Cancer Society about their policies on this issue, they brush him off and refuse his requests for an interview. Andersen further discovers that the commonly held view that diabetes can be attributed to, or at least worsened by, the consumption of sugar and carbohydrates is wrong. In fact, according to Dr. Garth Davis, one of the featured doctors in the film [1], the real consumption culprit for diabetes is actually eating red meat.

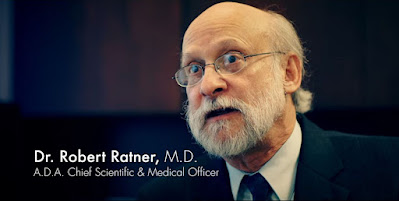

In this connection , there is a rather dramatic interview with Dr. Robert Ratner, the Chief Scientific and Medical Officer of the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Ratner adamantly refuses to blame the meat and dairy industry for worsening the health of diabetics. And when Andersen points out to him some peer-reviewed research articles that report finding a definite connection between meat and dairy consumption and worsened diabetic conditions, Ratner angrily shuts down the interview and leaves the room.

Of course, the discussion of this whole subject requires at least some consideration of the medical and pharmaceutical industries. One major problem with medical school education is that nutrition is not a significant theme in medical school curricula. I am not sure why this so, but perhaps nutrition is considered to have too-fuzzy boundaries and therefore to be outside the scope of “hard science”. At any rate, doctors coming out of medical school are not trained to be knowledgeable about nutrition and thus are not knowledgeable about the relative merits of plant-based and animal-product-laced diets. The clear benefits of following a plant-based diet are overlooked by most doctors.

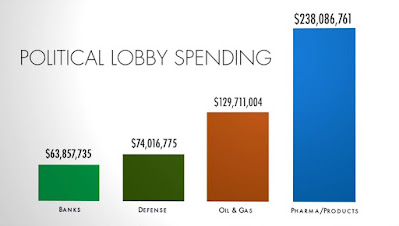

Another, more general concern is that the medical industry appears to be more interested in treating patients long-term than in preventing illness in the first place. This is also true of the pharmaceutical industry. Of course there are financial payoffs for following this path, but I doubt this is an explicit strategy on the part of these two industries. Nevertheless, this is a problem, and as the film shows, there is a simple path to follow that would reduce the occurrences of many long-term illnesses and thereby address this problem – following a plant-based (vegan) diet.

Expanding on these experiences and other evidence present in the film, the filmmakers of What the Health come out and explicitly recommend that, in order to have a healthy life, everyone should adopt a plant-based diet. They discuss with medical experts who debunk the commonly-held notion that a plant-based diet will be short of protein. In fact a plant-based diet provides plenty of protein, roughly just as much as a typical meaty diet. And it is worth pointing out, as is mentioned in the film, that there is nothing sacred about the protein in meat – all protein originates from plants anyway. Animals just recycle it.

They then show a number of muscular athletes and bodybuilders who attest that their physical prowess is significantly enhanced by their vegan diets.

Overall, What the Health is a well-made and usefully informative documentary that is well worth seeing. Its message is more emphatically told than is that of its companion piece,

Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret. However, from a pure filmmaking perspective, I liked Cowspiracy a bit more, because What the Health has more continuous sequences of “talking heads” that would have benefited from some more brief insertions of context-setting commentary on the part of Kip Andersen that would have smoothed the pace. Nevertheless, I recommend that you see What the Health and heed its advice [2].

Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret. However, from a pure filmmaking perspective, I liked Cowspiracy a bit more, because What the Health has more continuous sequences of “talking heads” that would have benefited from some more brief insertions of context-setting commentary on the part of Kip Andersen that would have smoothed the pace. Nevertheless, I recommend that you see What the Health and heed its advice [2].Notes:

- Other prominent, supportive doctors featured in the film include:

- Dr. Neal Barnard (see Forks Over Knives (2011))

- Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn (see Forks Over Knives (2011), The Game Changers (2018))

- Dr. Kim A. Williams

- Dr. Michael Greger

- Dr. Michael Klaper

- Dr. Neal Barnard (see Forks Over Knives (2011))

- See also my reviews of

- Eating, 3rd Edition (2009)

- Forks Over Knives (2011)

- The Game Changers (2018)